FROM FLESH TO DATA

GENERAL INFO

- LOCATION

-

Venice Architecture Biennale. Spanish Pavilion, Giardini dell'arsenale

- DATE

-

18/05/2023 to 26/11/2023

- Curated by

-

Eduardo Castillo–Vinuesa, Manuel Ocaña

- TYPOLOGY

-

Research / Exhibition

From Flesh to Data: Non-Human Intelligence and Artificial Stupidity

From Flesh to Data is a commission for Foodscapes, the curatorial proposal for the Spanish Pavilion at the 18th Venice Architecture Biennale, curated by Eduardo Castillo-Vinuesa and Manuel Ocaña. Foodscapes is a journey into the architectures that feed the world, from the domestic laboratories of our kitchens to the vast operational landscapes that nourish our cities. At a time when energy debates are more pertinent than ever, food remains in the background, yet the way we produce, distribute, and consume it mobilizes our societies, shapes our metropolises, and transforms our geographies more radically than any other energy source.

Through an audiovisual project of five films, an archive as a recipe book, and a public program of events and collective research, Foodscapes explores the present of our food systems to look to the future and wonder about other possible models, ones capable of feeding the world without devouring the planet.

Weavers of Fishing Nasas women's Association. Puerto de Corme, A Coruña. Photo, Pedro Pegenaute. 2023

Thinking Territories, Tentacular Landscapes

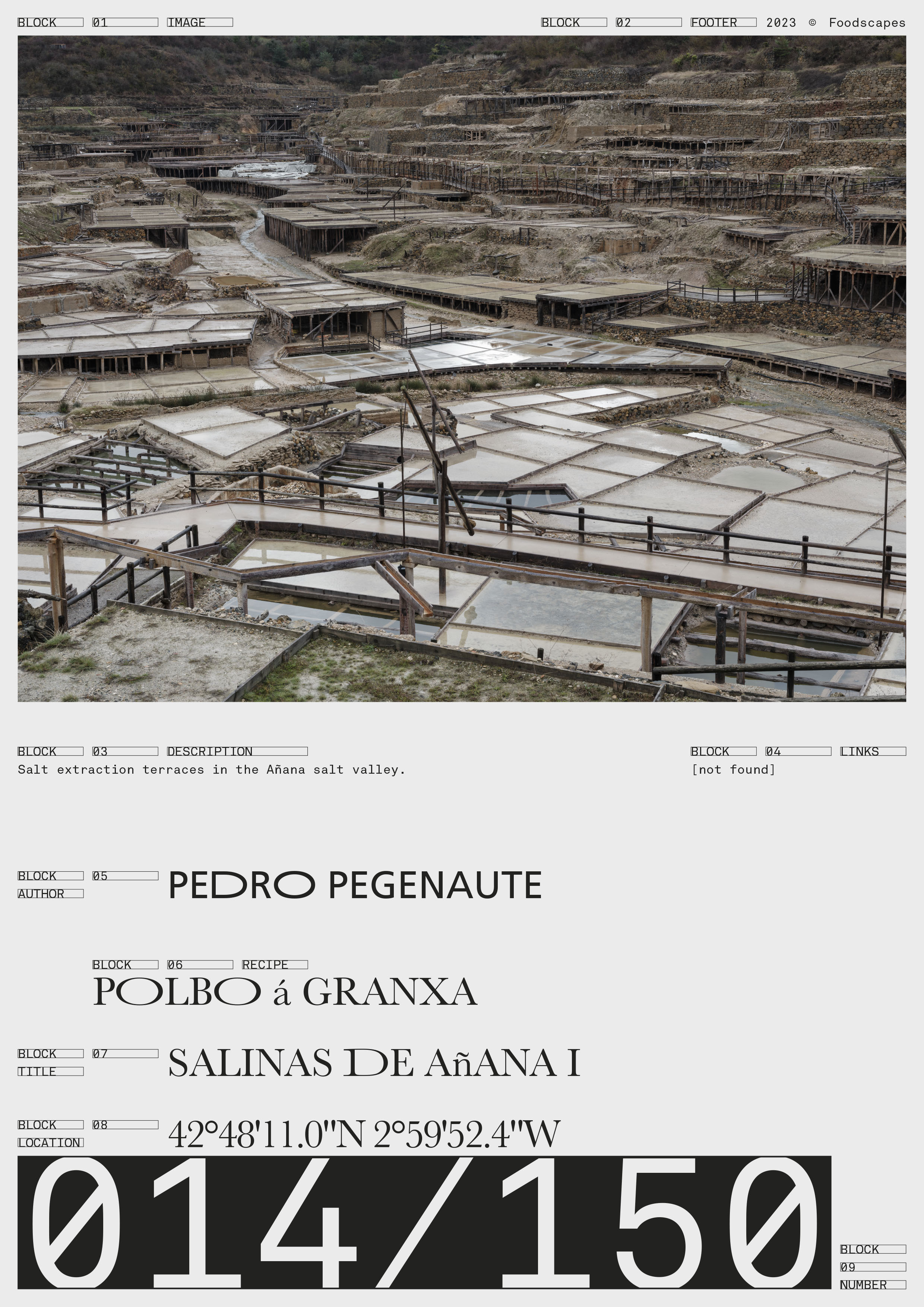

Seen from the air, Spain’s northwest coast is full of entrances and exits, estuaries, and firths where hundreds of rivers meet the sea, like tentacles or watery arms that connect the marine and the terrestrial. These two masses form a complex landscape carved in stone, filled with water, and lashed with strong winds and heavy storms. Such an intricate and sinuous relationship between two worlds (ocean and land) produces one of the most fascinating regions in the country, a universe with an immense diversity of life forms, but also of cultures, stories, and mythologies. The territory is itself a great organism, a non-human body that changes, digests, breathes, and thinks. Yes, it thinks, with a strange brain composed of mineral and salt, of vegetation, moss, lichens, and other species from the different kingdoms that populate its tissue.

If we follow a general definition of “intelligence” as the capacity for abstraction, self-awareness, learning, and emotional knowledge, or as the ability to perceive or infer information and to retain it as applied knowledge, we could say this landscape not only thinks but that it is fully intelligent. Perhaps this term, intelligence, a quality unfairly appropriated by human beings, lies at the center of multiple contemporary crises, delaying and precluding new ways of multispecies existence on our severely damaged planet.

Non-Human Intelligence

There are many questions that we must ask when faced with the belief that only our way of reasoning shapes the standard of intelligence for every organism (or superorganism, like an ecosystem). So, who is, or what is, intelligent? What are the material conditions necessary for intelligence to emerge? And who has the authority and heuristics to contend that another being is or is not intelligent? To many other contemporary thinkers, intelligence is everywhere, from the flying spores that reproduce plants to the pores on the skin of mammals: from the legs of insects to the sounds of whales.

Intelligence is life in action, its infinite forms, and relationships. It is not only that the world, Gaia, is itself intelligent, but rather that intelligent world. It is the process that makes up the semiotic-material environment of which we are a part (we are not “surrounded” by a milieu, we are that milieu). If we want to rethink post-anthropocentric relations with otherness, propose new forms of coexistence, and face ecological problems, perhaps we should start by abandoning the idea that intelligence is human only. And we need to do it for real. To fully understand and appreciate non-human intelligence, we have to embody that change of view. The very term, intelligence, is every day more entangled in our contemporary culture. We link it to technology, data management, and production systems, which must be uprooted, claiming instead other ways of inhabiting the world that think within the world, make worlds, world worlds themselves, and infuse them with meaning in a way that exceeds human standards and models. One way to get around the problem of intelligence could be to eliminate the term altogether (along with many others), as some radical behaviorists believe. This full erosion of the term, although extreme, raises questions not only about how it is used, but also about all the associated ideas, behaviors, or characteristics that emanate from a structurally speciesist, masculinist, western, and extractivist perspective.

Decentering the anthropos is not enough to overcome the lethal ideals of humanism in favor of a genuine multispecies alliance based on the productive and immanent force of all human and non-human life on Earth. What is crucial is a profound reconceptualization of subjectivity that does not confuse it with rational and conscious human autonomy, or with neoliberal, self-referential, and self-indulgent individualism, but recognizes our historical, material, and situated embeddedness with non-human agents as always already constitutive of our dynamic identities. We need to visualize the subject as a transversal entity encompassing the human (including the millions of symbiotic microorganisms that compose it), animals, fungi, plants, bacteria, and the planet as a whole.

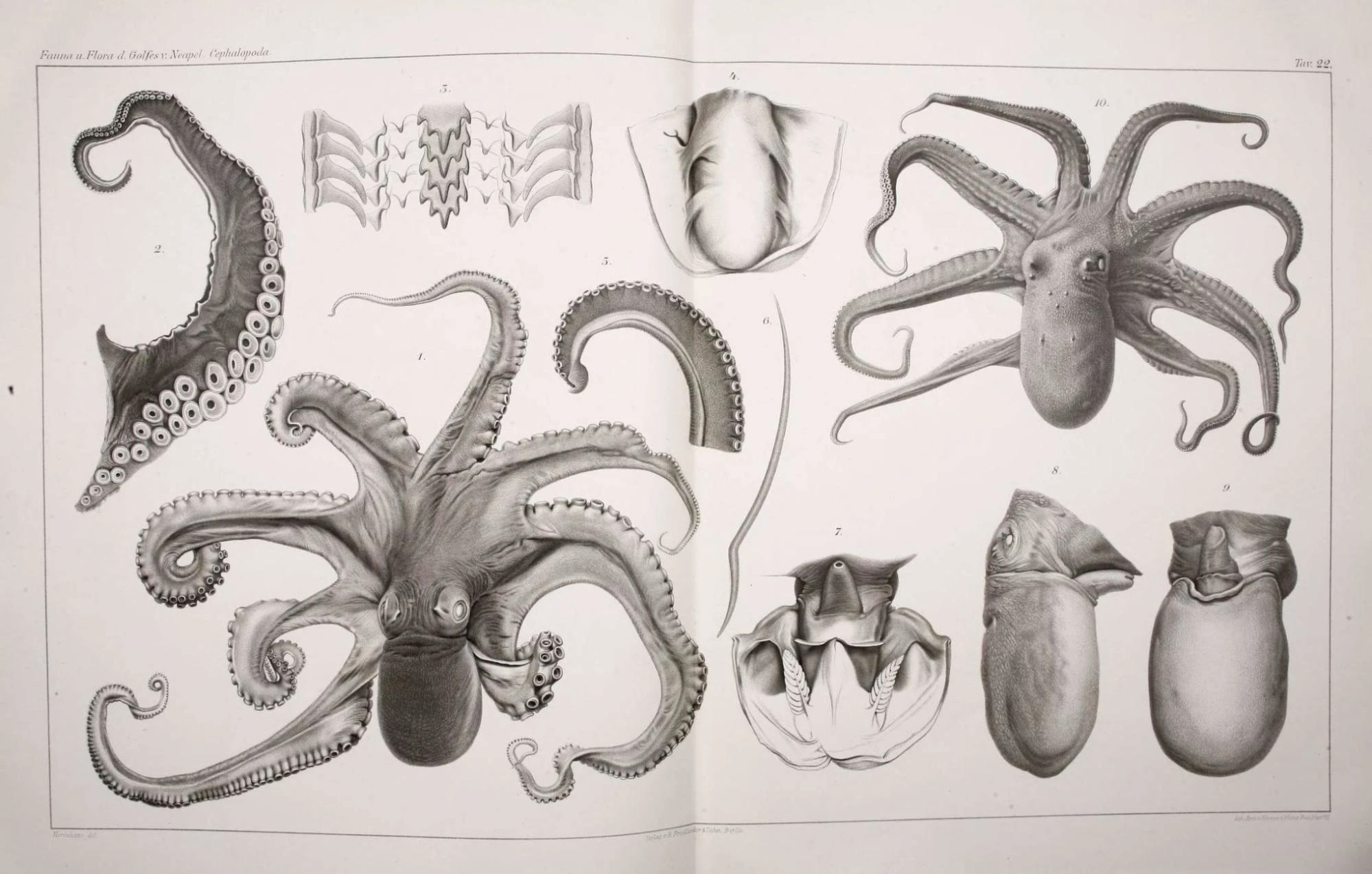

Jatta, G. J. Cefalopodi viventi nel Golfo di Napoli: Fauna u. Flora des Golfes von Neapel. 1986

Intelligence, Monstrosity, Vulnerability: The Octopus

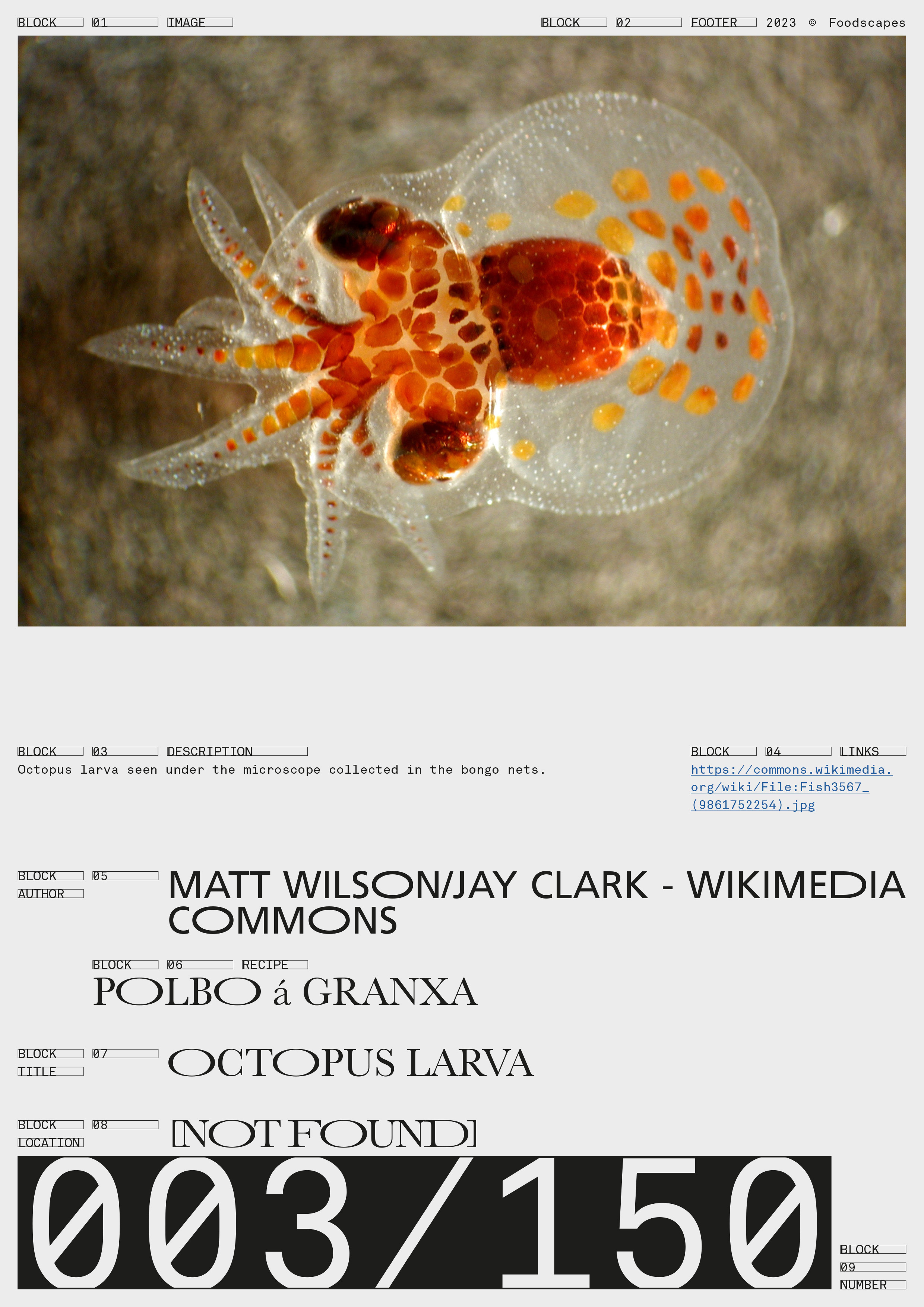

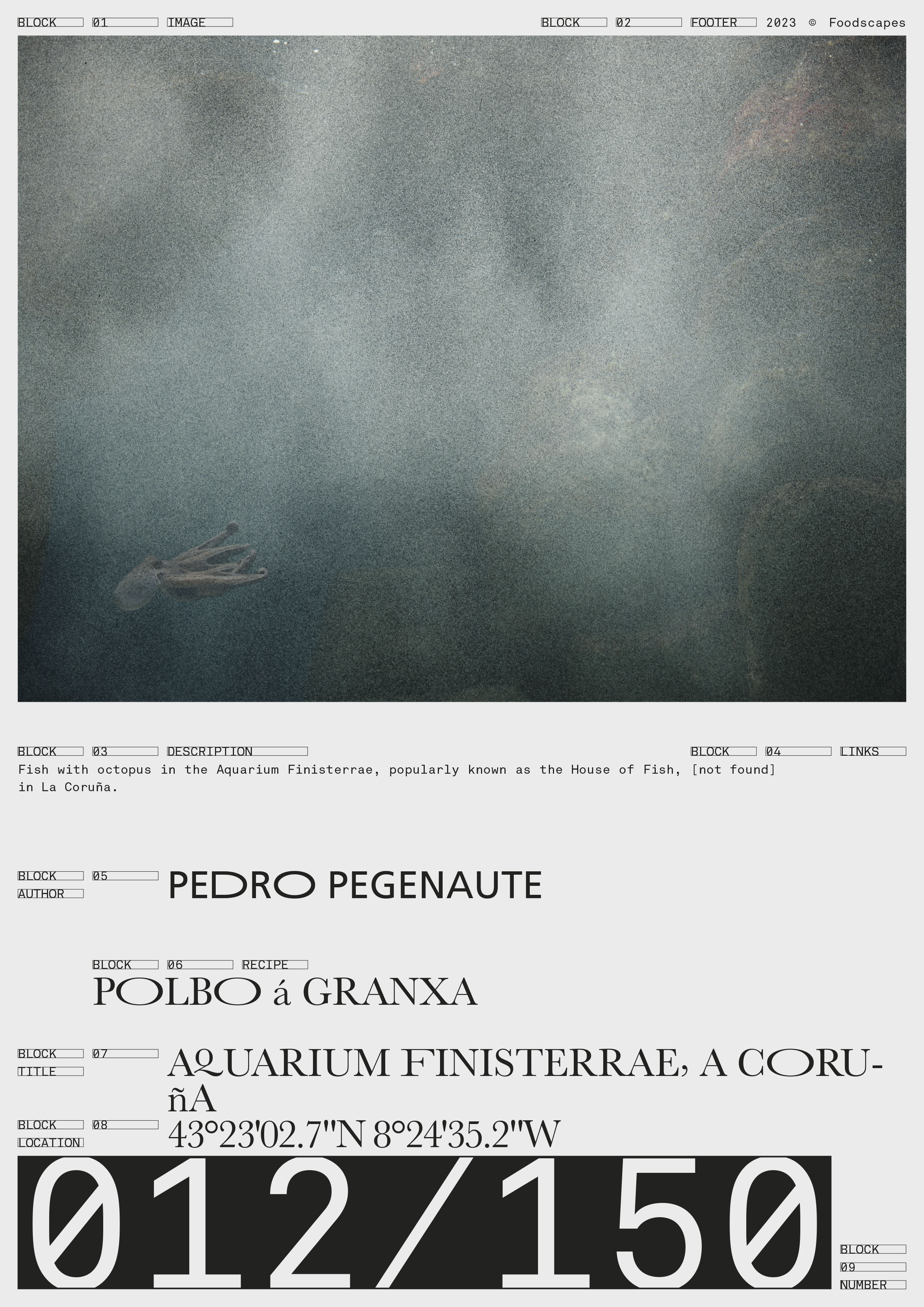

As with the rest of the cephalopods, octopuses lack a torso or intermediate part. Their tentacles appear directly next to their head. Their soft body is capable of rapidly changing shape and texture, allowing them to slip through small ducts or cracks. With a complex nervous system and excellent eyesight, they are considered one of the most “intelligent” and behaviorally diverse invertebrates. But still, even when they are said to possess a very complex “alien intelligence,” their cognition is generally evaluated against a human or humanized quality, expected to perform certain actions that resemble us in ways deemed valuable by an all-too-human set of priors.1 Maybe we fail to see, without our narcissistic precondition, the complex intelligence that these beings (as every other being, each in its own terms) enact. And in that sense, we have to abandon the idea of linear, purely abstract, language-based, human thought, and go on to explore other “strange” ways of being intelligent that -like ours, really-- are embodied and embedded.

Octopuses are non-human. They are “strange.” Both these tentacled critters and the dark hollowed caves they inhabit seem to us uncanny and monstrous, and yet they are not alien; they are “natural,” if this concept still bears any meaning at all. As Morton would argue, “there is no static background. What we call "Nature" is monstrous and mutant, strangely strange to the end.” 2 Strangeness is a concept that still designates what is allegedly separated from the human, creating a division, an artificial abyss that disconnects us from the world. But nature has never been natural, and we must accept our own monstrosity. There are no environments isolated from the organisms that compose them, and that includes octopuses as much as it includes us.

Testoni, Matt (2022). Maori Octopus

Octopuses have been the protagonists of numerous cautionary tales about the dangers of the ocean. According to many narratives from across the world, these monstrous entities are nothing like us – they live and exist in a realm beyond our control, however much this may clash with the image of a human disaffectedly ordering Polbo á feira at any bar. If today they have been reduced to a commodity, historically they populated our fears and nightmares. The kraken is the manifestation of this animal turned into a monster, translated from different cultures into a humanized product of tremendous size, with a reputation for crashing ships and pulling them down to the bottom of the sea.

How can we challenge this narrow perspective and challenge the opposition to the monstrous? How can we think with the monstrous, from the point of view of the other (including the other within), avoiding the implicit violence and heroic narratives in which the human subdues animality, conveniently depicted as a threat?

For that, we must not only change and expand our idea of intelligence but also transform the place of the non-human, in-human, more-than-human, and other-than-human in our all-too-human stories. What if the kraken, instead of being death-driven, accompanies our marine voyages? What if, rather than sinking ships, it is capable of showing the infinite other forms of knowledge and diversity that live in the wondrous depths?

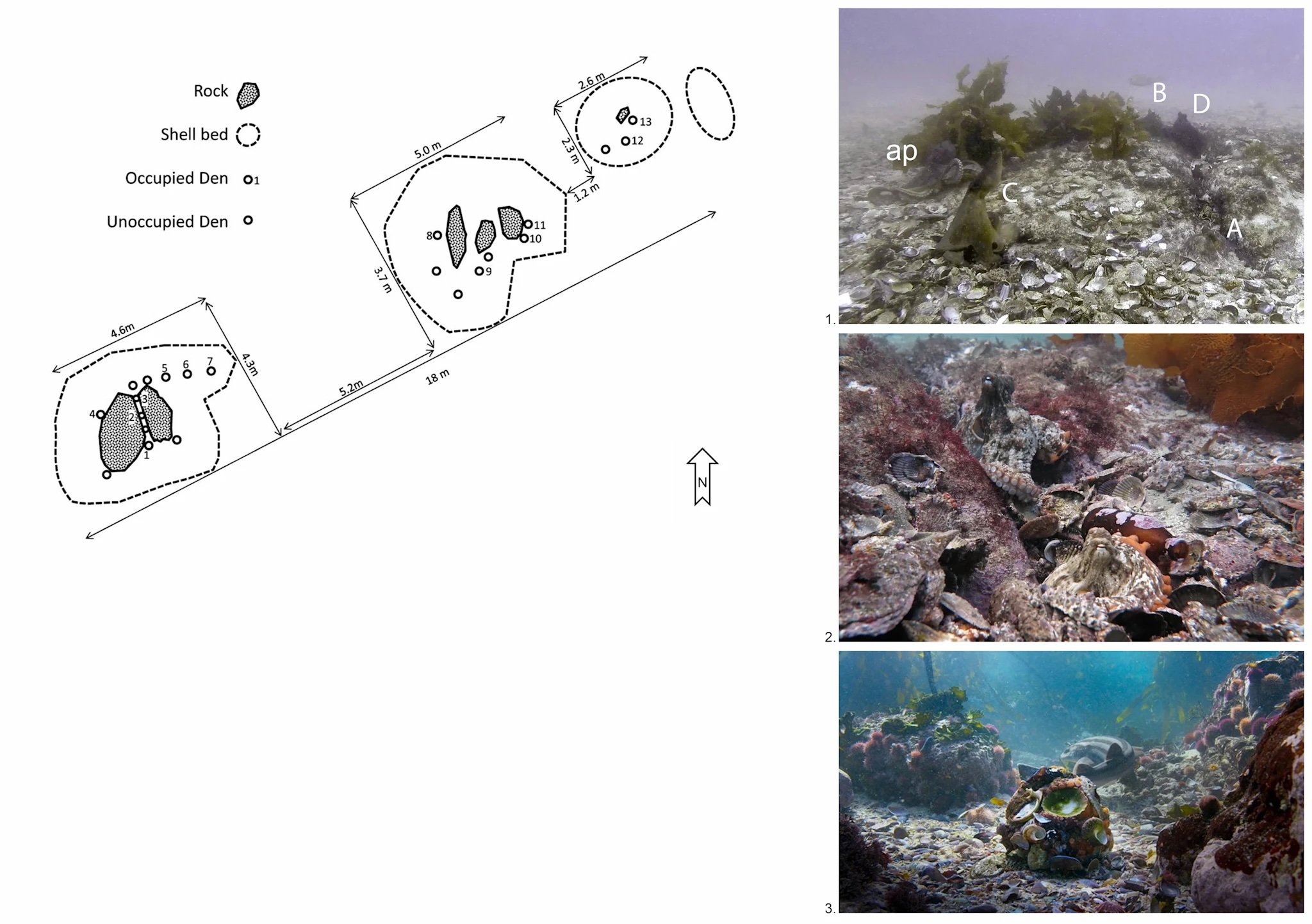

Diagram and images of Octlantis, the newly found octopus colony where different specimens cohabitate in a self produced environment. Image by Institute for Postnatural Studies

Unlearning, Decentralizing, Outbursting

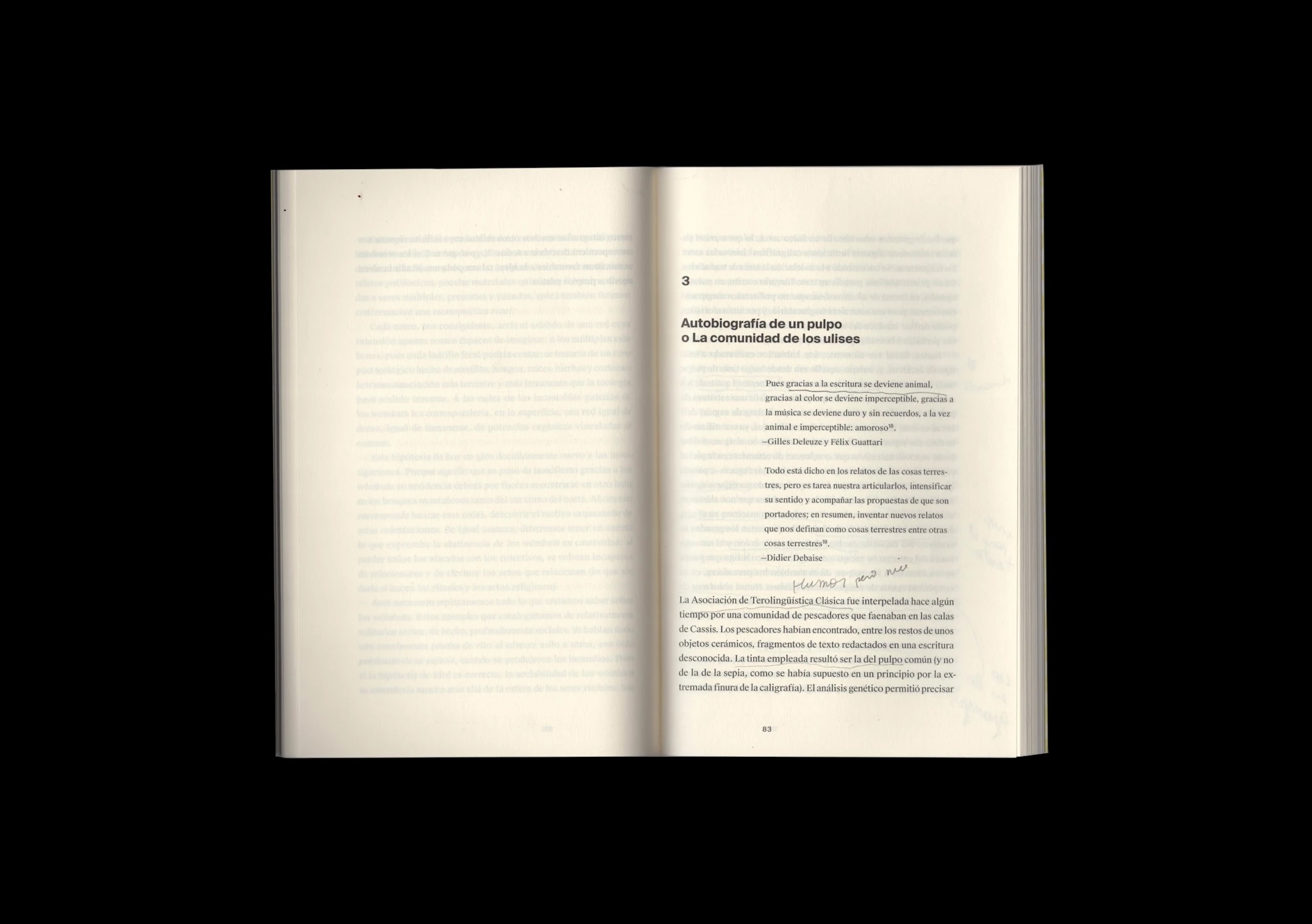

As science philosopher Vinciane Despret might ask, what would octopuses say if we asked them the right questions? By arguing that behaviors we identify as distinctly human do not properly belong to us, she invites us to stretch our ideas about what animals do, what they think about, and what they want and value.[3] There is no single attribute that belongs to all humans and humans only, be it abstract thought, technology, language, aesthetics, non-reproductive sex, ethics, or anything else.

Octopuses are the only animals that have a portion of their brain (three-quarters, to be exact) located in their tentacles. Every one of their eight tentacles “thinks” as well as “senses” the surrounding world with total autonomy, and yet each arm is part of the same organism. They are beautiful creatures, an incredible species that borders on the fantastic, displaying qualities that seem taken from a science fiction novel and, in fact, have informed several of them, animating all kinds of benign and evil tentacular monsters in literature. In her text “The Octopus in Love,” curator Chus Martinez describes how such beings enable us to imagine a form of decentralized perception and cognition, enabling us to understand the world in ways beyond human language.[4]

Octopuses are animals with short lifespans and minimal social interaction, a contradiction of the idea that high intelligence demands regular interaction with other beings. The essence of octopus intelligence lies in their ability to adapt to their environment. This competence relates closely to the loss of their protective shell in the course of evolution, allowing greater freedom of movement and flexibility at the price of newly exposed flesh.[5]

Scan of Autobiographie d'un pulpe, Vinciande Despret.

Trapped, Trapped, Trapped

When not characterizing octopuses as either “dumb nature” or hyper-intelligent beings, humans have been trying to catch them and eat them. To speak of octopuses and their relationship with the tentacular landscapes of the northwest Spanish coast is to speak about fishing and gastronomy, and about regimes of eating the other. In Spain, the marketing of octopuses dates back to the 12th century when monks of the Cistercian order were paid for the use of their properties not only in money but also in spices, including octopuses. Traded dry and in small pieces, they thus became currency of exchange.

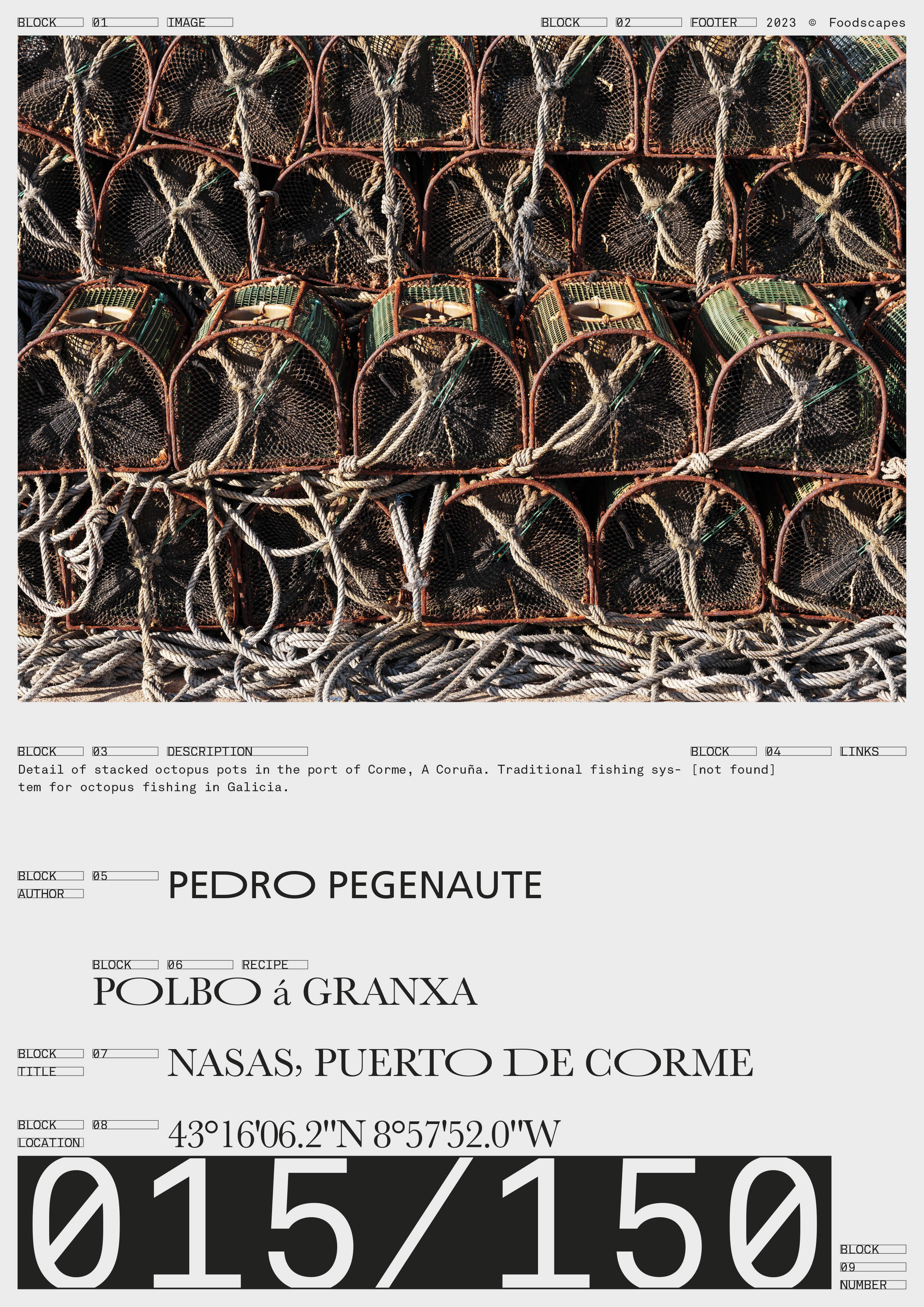

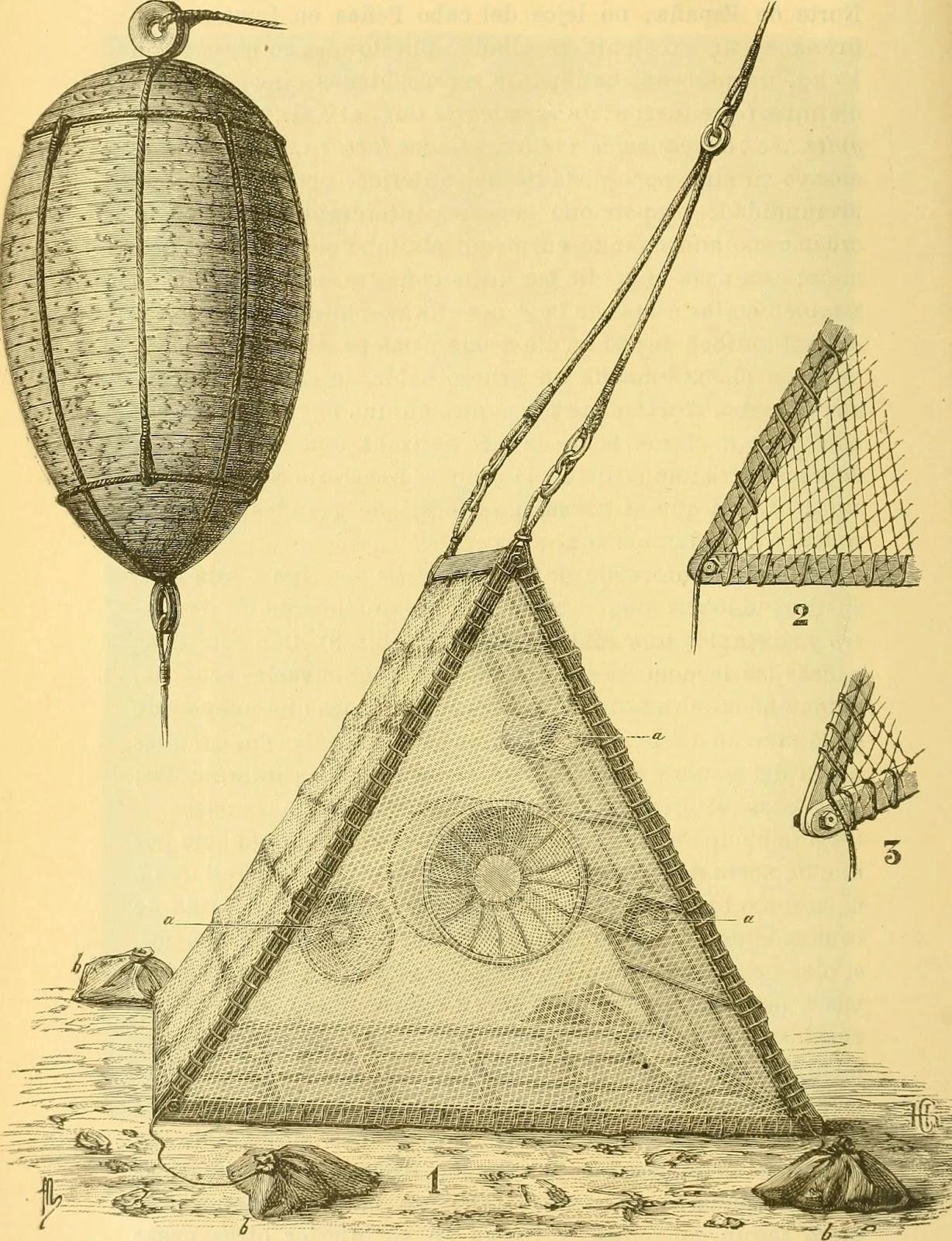

A major event in coastal fisheries was the introduction of traps. The use of these traps, or nasas, in Galician coastal economies has been documented since the 16th century.6 Of the many forms of fishing pots, the octopus catcher is one of the most complex. Net boxes, submerged ropes, and wicker tubes are not effective for them, as due to their advanced intelligence, they can easily empty the bait holder of its contents and flee. A plastic tube is placed between the ropes and knots of the fishing trap, the outer hole of which allows the entry of the animal. Their technicity and complexity go hand in hand with the species’ problem-solving skills, which challenge the designs and structures developed to trap them – an artificial architecture where the animals end up exhausting themselves, unable to escape, dizzy inside the plastic tubes and polished holes of the cage.

Polyhedral trap, in Annals of the Spanish Society of Natural History, 1891.

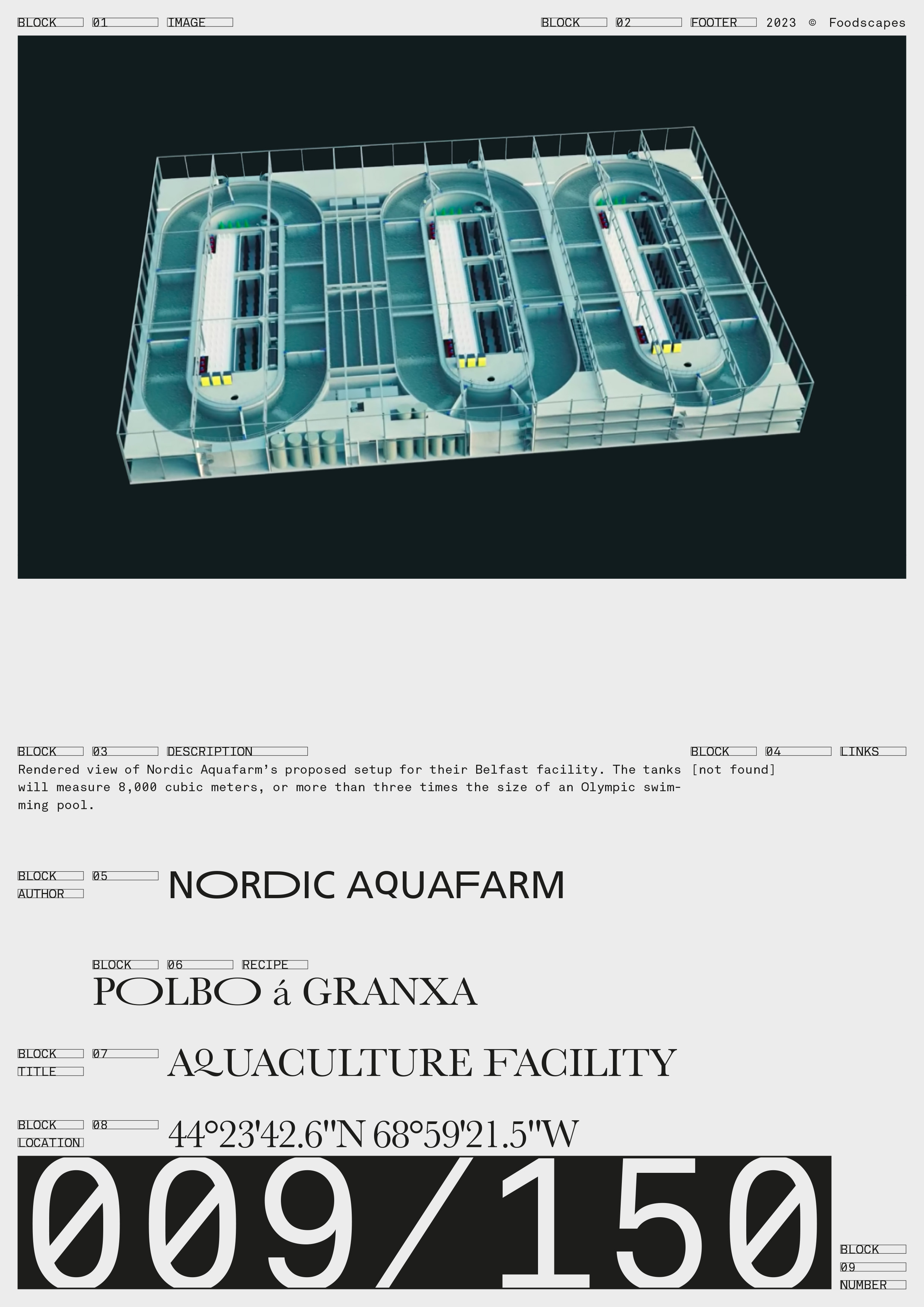

This form of octopus farming continues to evolve in the need to cover increased demand. Today, large-scale cultivation centers are being planned in response to an aquaculture boom that once again raises complex questions. These new octoculture farms will expand the capacity of companies to distribute octopus meat around the world. Again, intelligence is at the heart of the discussion, as many of the fish farms being planned will be managed with complex computer systems and artificial intelligence.

From Flesh to Data

Artificially intelligent beings have appeared as storytelling devices since antiquity, and have been common in fiction from many different cultures across time, generally as anthropomorphic characters, like the android or golem, raising many of the same issues that are being discussed in contemporary debates about the ethics of AI. But the study of mechanical or “formal” that lead up to Alan Turing's theory of computation, suggests that a machine, by shuffling symbols as simple as “0” and “1,” could simulate any conceivable act of deduction. By the 1950s, different visions for how to achieve machine intelligence emerged. Concurrent discoveries in neurobiology, information theory, and cybernetics led researchers to consider the possibility of building an electronic brain – a machine that thinks, or one that can learn and innovate.

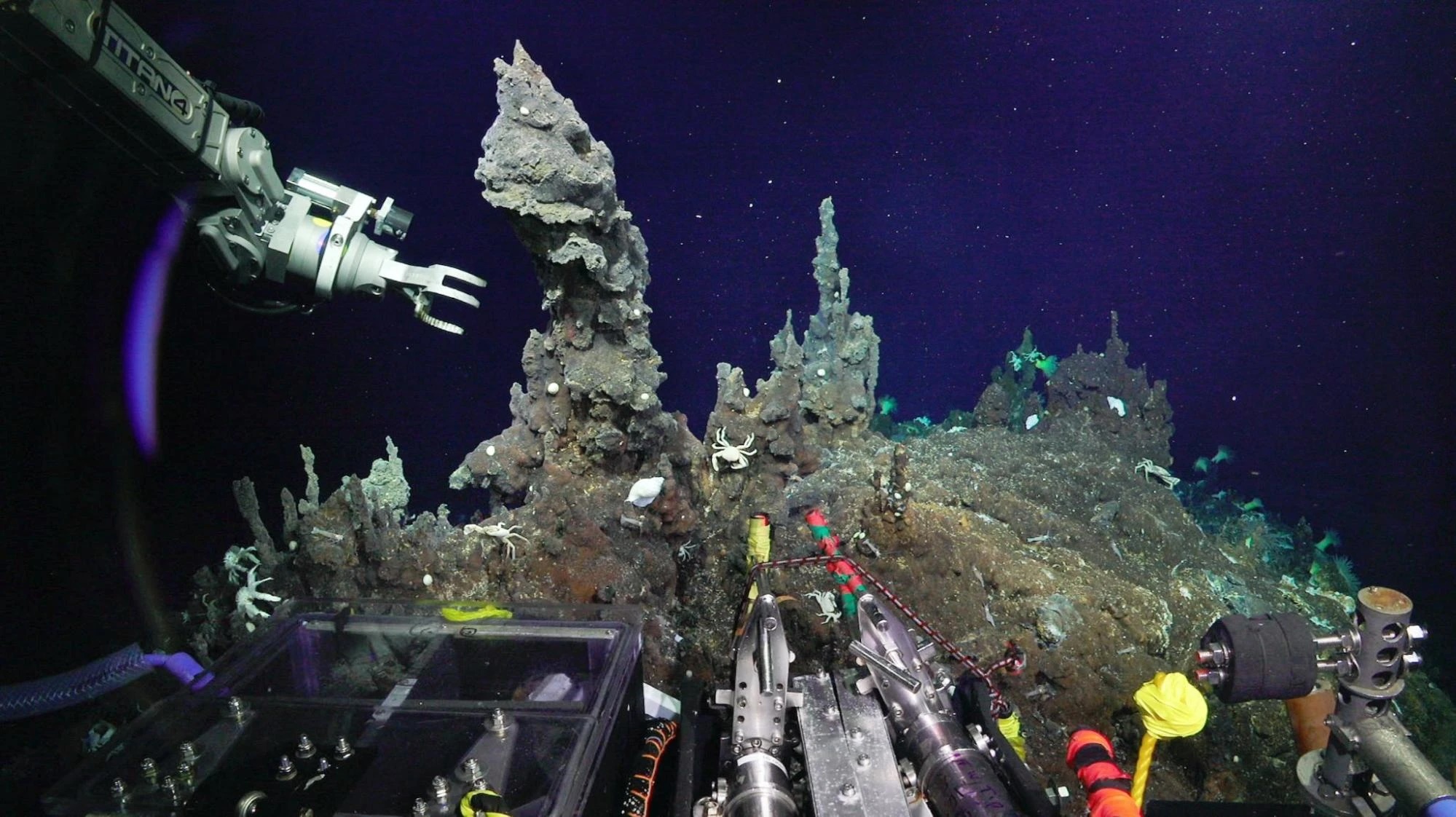

Research in artificial intelligence has grown exponentially, taking it to all fields of knowledge, the sciences, and the arts. Today, AI is everywhere. Machines attempt to predict the future. They reason, learn, create, and act by manipulating data whose scale exceeds that which individuals or groups of humans can analyze. And it’s being tested in the industry in the service of large projects and new infrastructure. The underwater world is a new frontier for big corporations to develop technological centers, as its pressure and temperature are more stable and energy efficient than at the surface. In other words, technology on land is exposed to many more external factors than at the bottom of the sea. And thus, the underwater world, once a place for mysterious creatures and mythologies, is becoming increasingly populated with heavy machinery like data servers that need to be cooled.

Northern Isles underwater data center, Microsoft. 2020

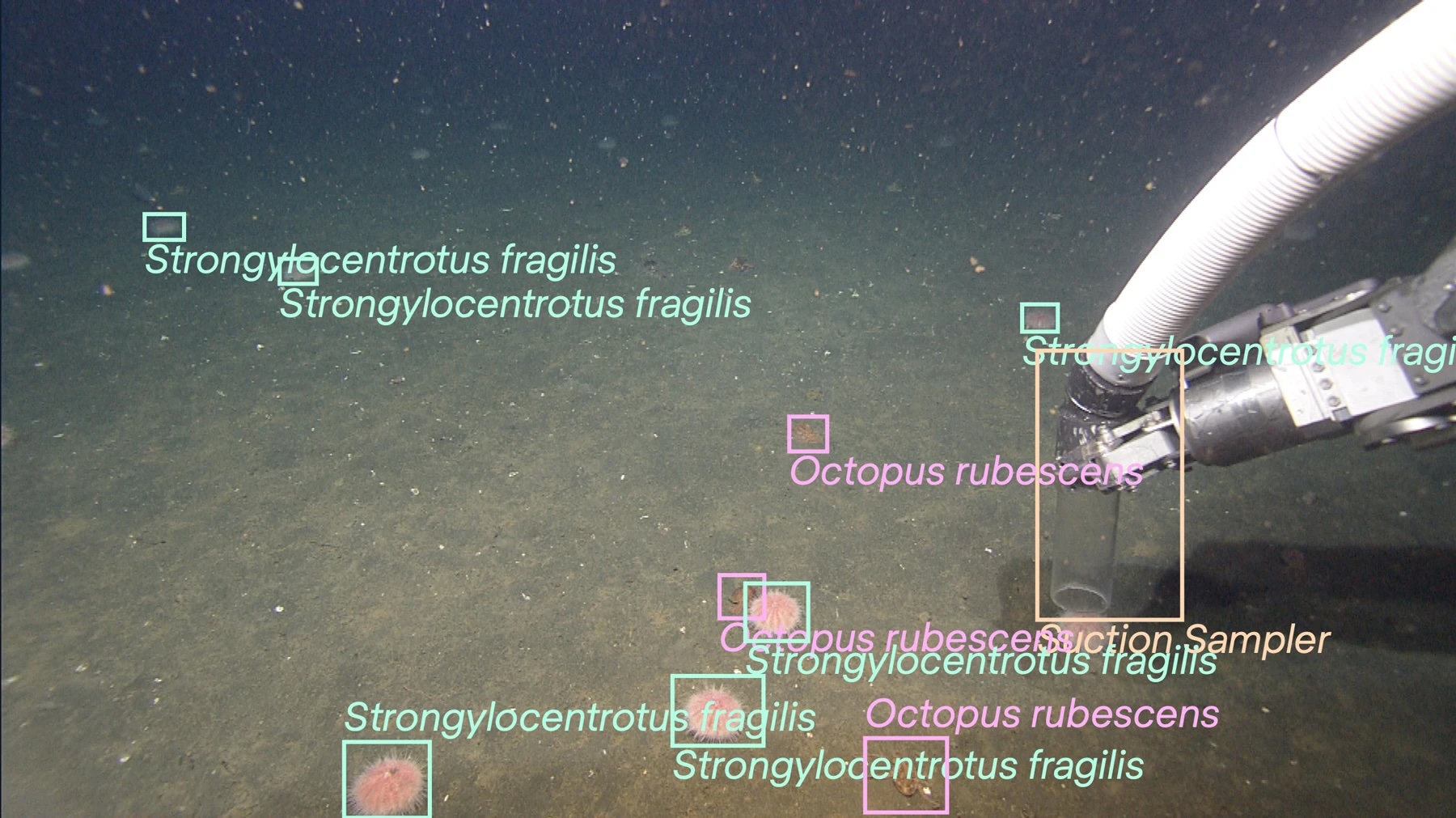

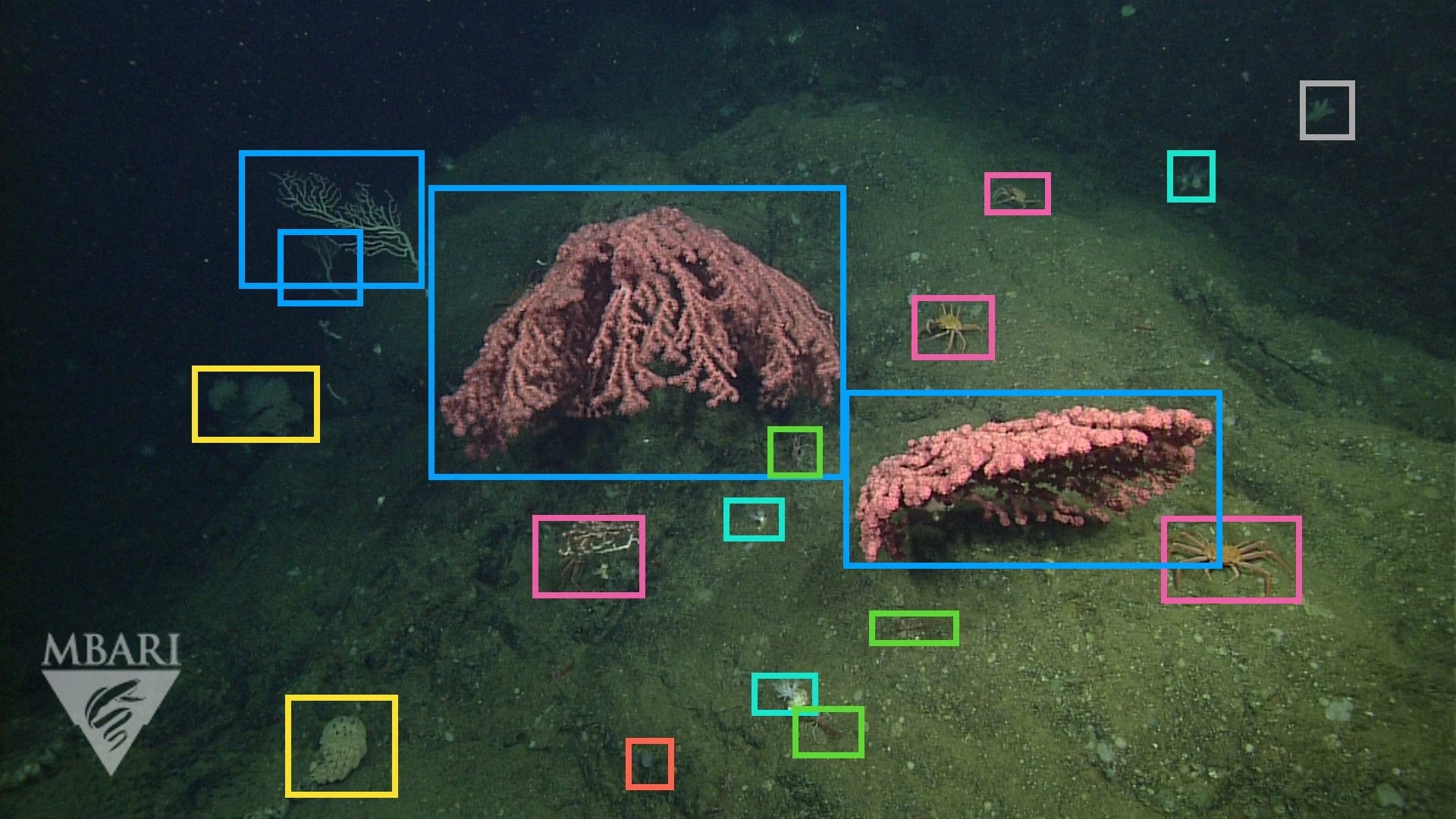

Underwater Farming: From Animal Intelligence To Artificial Stupidity

From animal farms to submerged data centers, the ocean is becoming a new landscape for production. In both cases, the sea becomes a new brain for non-human intelligences that are tested out of sight by most humans. Turned into a new cyborgian space between water currents, schools of fish, lichen, and algae, our coasts will be a new zone in which to question the term intelligence: what it means and to whom or what it applies. The use of predictive technologies and AI surveillance accounted for what artist Hito Steyerl calls “digital stupidity.” It’s a funny phrase, but its consequences can be dire. Contact tracing algorithms used, for example, during the COVID-19 pandemic in early stages, have been known to misidentify people, wrongly select virus carriers, and make mistakes in automated processes.7

SUBMERGED ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE INFRASTRUCTURES

Artificial intelligence needs parameters and data with which to operate, and these, generated by human beings, are fully ethically and politically charged. Certain AIs are defined as being operationally racist or sexist since the databases from which they extract material (information compiled both by government agencies, but also through private statistics, mass media, etc.) before being processed are rooted in extractivist, colonial, binary, and excluding structures (for instance, particularly in early stages of AI image recognition, since there existed a bigger database containing pictures of white people, for which the internet was simply more accessible, it was more likely that these technologies identified white people as human than Black, Indigenous, and People Of Color). Therefore, an AI is not, nor can it ever be, neutral. In his research project “Excavating AI” artist Trevor Paglen explores the politics of images in machine learning training sets and investigates how our human cultural biases influence machine learning.8 So maybe the so-called intelligence of IA is our own species' stupidity, recombined.

It is also important to note that different species of octopuses have different needs and requirements, so it is important to research the specific needs of the species you are raising and consult with experts in octopus care to ensure that the tank is appropriate for the species in question. The ideal architecture for an octopus would depend on several factors, including the species of octopus, its natural habitat, and the goals of the keeper or researcher. In general, an ideal architecture for an octopus would provide a safe and secure environment that allows the animal to exhibit its natural behaviors and provides adequate space, temperature control, and water quality. The architecture would also provide for the maintenance of proper water chemistry, adequate lighting and filtration, and access to food and other resources. If the octopus is being kept in a captive environment, such as a research facility or aquarium, it may also be important to consider the needs of the keepers or researchers, such as ease of access for maintenance and observation, and the ability to control environmental variables for experimentation or study. Ultimately, the ideal architecture for an octopus will depend on a variety of factors and will need to be tailored to the specific needs and circumstances of each individual animal.

It Is The Time Of Monsters: Wilderness

When understanding the newly blurred boundaries between the human animal, the non-human animal, and machines, it is necessary to rethink not only the idea of intelligence, but also nature and wilderness. Rethinking our non-human relations can’t involve a reinterpretation of the living creatures called "animals" only, but also another concept of the machine, of the semiotic machine of artificial intelligence, of cybernetics and bioengineering, and of the genic in general.[9]

This is because wildlife is seen as more natural, unaltered, and sustainable. Additionally, there is often a perception that wild animals live in better conditions, have more diverse diets, and are more adapted to their environment. On the other hand, farm-raised animals are often seen as being raised in controlled and unnatural environments and may be subject to inhumane conditions. These factors often contribute to the perception that wild animals are of higher value than those that are farm-raised. Humans may have a fascination with wild animals due to the idea of their natural existence and their ability to survive in the wild without human intervention. This can be seen as a symbol of strength, resilience, and freedom. Wild animals may also evoke feelings of awe, wonder, and mystery. Additionally, wild animals are often associated with adventure and excitement, which can add to their allure. Furthermore, some humans see wild animals as being closer to nature, which they may view as being pure, uncorrupted and closer to the essence of life. Generally speaking, wild animals are considered to have more freedom and are therefore seen as being more valuable, while captive animals are seen as being less valuable. However, this view is not universal, and many people believe that it is not fair to treat any animal differently based on where it lives or how it was raised. Ultimately, the question of fairness is subjective and depends on individual values and beliefs.

The monster has both tentacles and flesh, microchips and processors. It is neither natural nor artificial; it lives in the nooks and crannies of the depths but also in the metallic and plastic boxes of submerged computers. It lives and thinks between creatures on the seabed, among myths and data clouds. The monster is everywhere, we are now the monster, and we are living in monstrous times. We no longer have to continue chasing the dream of a world without us: we must inhabit responsibility and materialize new forms of coexistence for the human-animal-machine. Faced with an imminent and undeniable ecological crisis, the search for a solution and the call to change our current habits sometimes find themselves set back in the form of a utopian dream. This dream takes the form of nostalgia for a mythologized past, an Edenic state of existence in which humans lived in harmony with nature. However, as William Cronon writes in his article "The Trouble with Wilderness: Or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature," such an approach is flawed since it is based on the idea of a mythical boundary separating supposed inherent knowledge from nature of today’s society, a society that has lost access to this knowledge through the colonial act known as “civilizing.” We are now civilizing the oceans, colonizing their entrails, and manufacturing creatures under our parameters and needs. So we may as well abandon the romanticized idea of wilderness that actually led to its domination.

Jack Halberstam picks up where Cronon’s article left off in exploring the wild by further criticizing its colonial definition. Wild Things: The Disorder of Desire (2020) describes what the wild is not: “The wild is not the territorial equivalent of freedom […] the wild has its regulatory regimes, its concept of order, and its hierarchies and modes of domination.”10 Focusing on the epistemology of savagery, Halberstam argues that in its purest form, savagery is a way of existing outside of borders and order, while denying any attempt to impose such order.

Prompt: "Traditional ways of eating octopus in Galicia". Image by Institute for Postnatural Studies and Stable Diffusion

Learning From Octopuses' Dreams

Octopuses live in warmer waters, oceans turned into fabrics and farms, increasingly colonized and exploited. They, therefore, deserve to be given a new ontology, greater empathy, and a sense of kinship. Following Despret, what if octopuses, as early believers in metempsychosis, were frantic not to be able to guarantee the reincarnation of their souls due to overfishing and ocean pollution? And what would happen if, in a future managed by AI and logarithms, a farm’s animal care system failed, overcrowding their cages? What if the floodgates opened? What will wild octopuses think of their captive-bred mates? How will these science-breed animals approach the submerged data factories, with their emanations of heat and their metallic skins? Will they be angry, curious, afraid…?

If we are creating a new kind of octopus, as its cultural behaviors will be coupled with the captive environments, we need to consider an alternative form of knowing something more about them and how to look back, perhaps even scientifically, biologically, and therefore also philosophically, and intimately. In this new cyborgian landscape, maybe the dreams of octopuses recreate previous states of the cliffs, of the rock that housed their ancestors. Or maybe their dreams will be populated with data flows, colored squares of species recognition, machine learning algorithms, and plastic surfaces. To think of the new octopuses’ dreams, to think with monsters, to unthink far from human intelligence are possibilities for de-emphasizing human exceptionalism in favor of multispeciesism, of ecology. We, as humans, need to rethink cohabitation, coevolution and embodied cross-species sociality inside the troubled waters of contemporaneity. These newly bred octopuses can maybe show us the importance of recognizing differences, embracing strangeness, and engaging with significant otherness.

FOODSCAPES PUBLICATION

BIBLIOGRAPHY

-

01.

Hoffmann, C. H. 2002. Intelligence in Light of Perspectivalism: Lessons from Octopus. Ital Publishers

-

02.

Morton, Timothy. 2012. Ecological Thought. Harvard University Press.

-

03.

Despret, Vinciane. 2016. What Would Animals Say If We Asked the Right Questions?. University of Minnesota Press.

-

04.

Martinez, Chus. 2013. “The Octopus in Love”, e-flux journal #55.

-

05.

Hoffmann, C. H. 2002. Intelligence in Light of Perspectivalism: Lessons from Octopus. Ital Publishers

-

06.

Bañón, R., Otero, J., Campelos-Álvarez, J. M., Garazo, A., & Alonso-Fernández, A. 2018. “The traditional small-scale octopus trap fishery off the Galician coast (Northeastern Atlantic): historical notes and current fishery dynamics”. Fisheries Research, Vol. 206: 115-128.

-

07.

Steyerl, Hito. 2017. “Gott ist doof.” On Artificial Stupidity”. HKW, lecture.

-

08.

Crawford, Kate, and Paglen, Trevor. 2019. Excavating AI: The Politics of Training Sets for Machine Learning. Berkeley Center for New Media.

-

09.

Derrida, Jacques. 2008. The Animal that Therefore I am. Fordham University Press.

-

10.

Halberstam, Jack. 2020. Wild Things: The Disorder of Desire: Perverse Modernities. Duke University Press.

CREDITS

- EDITED BY

-

Eduardo Castillo-Vinuesa, Manuel Ocaña, Fundación Arquia (FQ), Ministerio de Transportes, Movilidad y Agenda Urbana (MITMA), AC/E

- GRAPHIC DESIGN

-

N-E

- CONTRIBUTORS

-

Common Accounts, Guillermo Fernández-Abascal + Urtzi Grau, Iván L. Munuera + Vivian Rotie + Pablo Saiz, Urbanitree + Manual Bouzas, Lucía Jalón Oyarzun, Aldayjover, Institute for Postnatural Studies, Lucia Tahan, C+ Arquitectas, Federico Soriano

- EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

-

Ana Ara

- PHOTOS

-

Pedro Pegenaute