The London Health Exhibition. Consuming sterilisation for the home

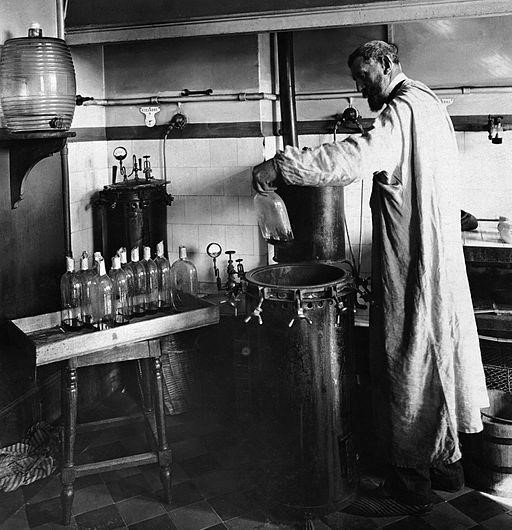

Simultaneously, the spatial configuration of sterilisation started to take hold in Europe as the Hygienist movement gained strength. In 1884 the

London Health Exhibition Francis Galton s Anthropometric Laboratory at the International Health Exhibition, London. Archives of Dutch Psychology

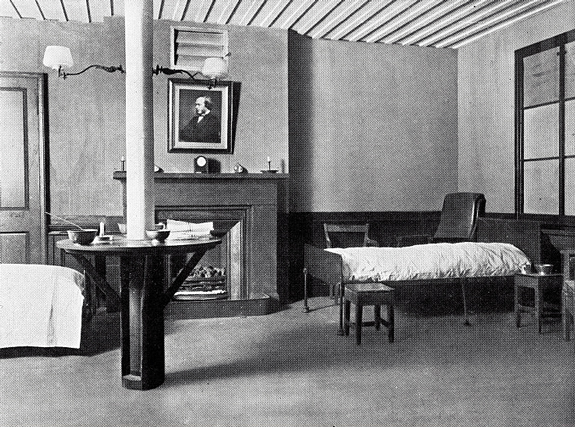

, with Pasteur among the attendees, gathered in one place the multiplicity of devices and practices that were emerging around the idea of sterilisation. From pasteurised milk to ventilation and drainage systems, from spotless white furniture to models of hygienic living rooms and even the first Chinese menu, were all introduced to London society. Designs for the home had a prevalent place in the exhibition, as the main attraction was a life-size reconstruction of the medieval old London street brought into contrast with Victorian buildings furnished with modern drainpipes and ventilators.

[7] The exhibition was in a way a kind of hygienist IKEA of the 19th century where middle class families walked around the isles looking for gadgets to ensure the cleanliness of their homes, not only out of concern for their health but also “as a talisman against downward social class mobility”.

[8] A visit to the London Health Exhibition would show how the sanitation movement turned domestic design into a form of preventive medicine.

[9] Furniture was lifted from the ground, ornaments faded and furry mats turned into sleek and smooth surfaces, illusioning our homes as domestic laboratories.

Sealing the interstices. How sterilization has influenced design to our days

Developments in science, architecture and design over the last hundred years have seen the biopolitical project of sterilisation become so widespread and refined that we have become unaware not only of the presence of microbes but also of the strategies that have allowed their invisibilisation. We have entered what Sennett calls the “politics of indifference” [10], in which microbes remain outside our daily concerns and consequently of the interests of design.

An example of the insidiousness of the borders and protections that we have built around us is the use of rubber in pipe seals and window joints.

Natural rubber Natural rubber

, which was imported from the colonial campaign, started being used in 1894 for the design of surgical gloves in England following the bacteriological research of Pasteur, Koch and Lister.

[11] Through later treatments of the material, natural rubber —originally obtained from rubber tree (

Hevea brasiliensis) — became increasingly synthetic, lowering costs and expanding its production capacities which prompted its use for many functional elements of everyday design. The same rubber that was used for surgical gloves has facilitated the perfectioning of the Victorian obsession with hermetic homes by sealing the building’s “skin”. Responding to the omnipresent, invisible threat of undesirable microorganisms, rubber seals also become invisible and omnipresent in the design of our houses. Rubber infiltrates itself in the in-between spaces of buildings, filling any possible spaces of interaction with its barren materiality. The current interior aesthetic of white finishes and polished surfaces is sustained by the perfectly-designed pieces of rubber behind it. Beyond their unquestionable functionality, these contribute to our feeling of confidence and comfort which we get from the idea that our spaces are protected and conveniently isolated from any penetration from the outside. This feeling comes to be taken “as a guarantee of individual freedom and action,”[

12] as if we could live and act separately from other organisms. In this way, rubber becomes a facilitator of the biopolitical project of sterilisation, along with its practices and imaginaries.

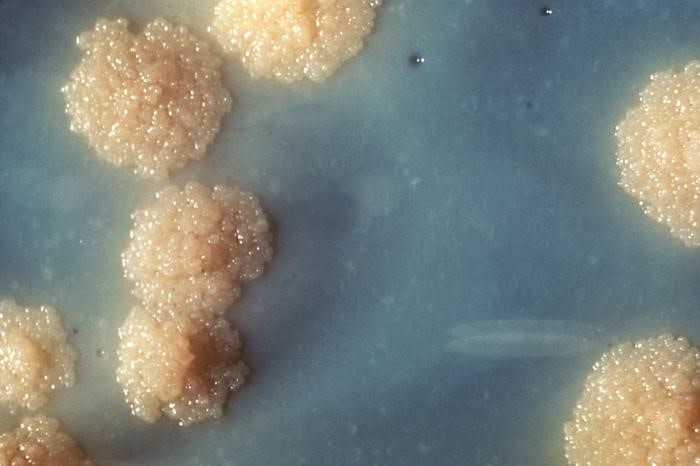

Since the times of Pasteur, microorganisms have been recognised within architecture and design only as pathogens. The forms, materials and technologies of design have been selected and developed to eliminate anything microbial through methods that are non-selective; they not only kill pathogens, but also all other microbes which are beneficial to human health and to whole ecosystems. The sterilisation of the built environment has brought it out of balance and disabled its capacity to self-regulate. Beyond its material consequences, the narrative of sterilisation has resulted in the creation of a series of dichotomies for the classification of bodies and spaces: inside/outside, pure/contaminated, wild/domesticated. Such dichotomies become both ontological and physical borders, leaving companion species inside and those deemed uncontrollable and undesirable outside. According to Tsing, “with the fetishisation of the home as a space of purity and interdependence, extra-domestic intimacies, whether within or between species, seemed archaic fantasies.”[13] In this way, architectural spaces and in particular “the home cordon off inter- and intra-species love,”[14] preventing our appreciation of the complex relationships that we as human beings establish with other non-human agents constituting our bodies and our environments. We argue that to overcome this binary heritage of design and to understand how relations between organisms may allow spaces to self-regulate, we have to look at the behaviour of the microbial cosmos through a different microscope.

Lynn Margulis. A different look into the microcosmos

If Pasteur and Koch gazed through the primitive lenses of their primitive microscopes at invisible “enemies”, Lynn Margulis saw a very different picture when staring through the improved electron microscope. Looking closely at the eukaryotic cells which make up animal and plant biology, she hypothesised that their small organelles came from long-term relationships of coexistence. Margulis’ theory of the origin of eukaryotes led to a new hypothesis for evolution which she called symbiogenesis, claiming that the origin of new forms of life was primarily the result of symbiosis. Bacteria, our fundamental symbionts, infiltrate all our ecosystems, including our own bodies. Healthy underarms, clean mouths and functional guts all enjoy unconscious symbiotic relations with all sorts of bacteria. Rather than self-contained individuals, we are “walking assemblages” of different kinds of organisms. This turns on its feet the simplified and biased perception of microbes as enemies we inherited from the 19th century. Margulis’ findings pose a challenge to the notion of the individual and the human species and therefore to all the disciplines founded on anthropocentric principles. What are the consequences for domestic design when its unit of measurement is no longer only the human figure but its tentacular, sticky and flamboyant associations with microbes?